Two media workers die every week, according to IFJ report

Jim Boumelha analyses 30 years of the IFJ killed list.

By Jim Boumelha, IFJ honorary treasurer and NUJ NEC member

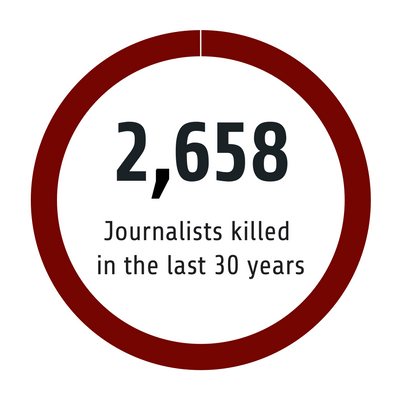

2,658 journalists killed in the last 30 years

© IFJ

When the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) published its first annual report of killed journalists in 1990, very few anticipated that the "journalists killed list" would still be going 30 years later, spanning the entire globe.

The grim numbers that shocked the world were a stark reminder of what Chris Cramer dubbed "a hunting season of journalists". Over these years we paid almost every week with the life of a reporter, a cameraman or support worker, and unless it was the case of a well-known Western correspondent, the world barely noticed.

The IFJ was the first organisation representing journalists to raise the alarm over their killing and chart their fate every year as they were targeted with impunity in every corner of the globe, brutalized, gunned down, kidnapped and done to death by the enemies of press freedom. The IFJ casualty toll included all journalists including freelance as well as support staff such as drivers, fixers and translators who died during newsgathering activities. This was unique in giving a fuller picture of the extent of casualties within the media workforce. Many years later, other press freedom organisations launched their own reports, which did not add much except, produced different numbers that made it more difficult to have an authoritative precise figure.

At the time we started counting in 1990, we listed 40 journalists and media workers killed in that year. This was at a time when raising a white flag and writing TV in masking tape on a vehicle might help keep one safe. Some believed that this was merely a blip. Sadly this proved not to be. When you aggregate all these numbers, the total adds up to a staggering 2658 killed in the last thirty years. This comes to about two journalists or media workers dying every week.

Over 50 per cent of journalists were killed in the ten most dangerous top spots featuring countries which suffered war violence, crime and corruption as well a catastrophic breakdown of law and order. Iraq (339 killed) came top followed by Mexico (175), Philippines (159), Pakistan (138), India (116), Russian Federation (110), Algeria (106), Syria (96), Somalia (93) and Afghanistan (93).

These numbers also show that there has not always been a consistent targeting of journalists spreading year in year out, except for a few countries. The most murderous years were 2006 and 2007 with 155 and 135 killed, respectively. They reflected the height of the Iraq war and the sectarian bloodbath that ensued with 69 and 65 (almost 50%) killed, respectively, in each of these years.

In Iraq, which topped the table and acquired the moniker of the most murderous country in the world for journalists, killings of journalists were rare in the first decade of this period. It was not until 2003, at the onset of the Anglo-American invasion, that the numbers started stacking up.

Similarly in Afghanistan the numbers (93) reflect the aftermath of the US invasion in 2001. The link between deadly conflicts and a spike in the murders of journalists was also apparent in the civil war in Algeria which kicked off in 1993 and ended in 1996 – the bulk of the 106 killed journalists died in a short period of three years. This was also the case of the war in Syria which started in 2011 and is still ongoing resulting in 96 killed journalists for the last nine years.

Other conflicts like the long-running insurgency in Somalia has propelled the country to be the most murderous in Africa for journalists and the 9th on the IFJ top list. In the Indian sub-continent, murders of journalists in Pakistan (138) and in India (116) have featured almost every year in the killed list since 1990, making 40 per cent of the total death in the Asia Pacific region.

Equally the pattern of the killing of journalists in Mexico, in most cases at the hands of organised crime, made this country the most dangerous in Latin America, featuring on the IFJ list every year and sometimes with double-digit numbers. Bearing in mind that journalists have been targeted in big numbers since the 1970s and 80s, Mexico will remain the most dangerous place for journalists in the planet.

The patterns of regional variations also lift the veil on how these killings have evolved over the years according to specific variables. The Asia Pacific region comes first with 681 killed journalists, followed by Latin America with 571, the Middle East with 558, Africa with 466 and Europe with 373.

There is no single explanation as to why journalists are targeted, but one of the principal causes has always been wars and armed conflicts where journalists who report on them are exposed to injury, kidnapping or worse. In recent years a novel threat to journalists has emerged with the involvement of terrorist organisations, many operating in the Middle East region. In the case of the murder of journalists at Charlie Hebdo it proved they can strike in any part of the world.

In other regions it is not war but crime barons and corrupt officials who lead the slaughter. The latter includes civilian government officials backed by allied paramilitary groups without forgetting anti-government forces.

Historically a region like the Middle East experienced a relative calm during the first ten of the 30 years. Only 16 journalists were killed between 1990 and 2020 and it is not until the invasion of Iraq in 2003 that the numbers started spiking up.

The accumulated statistics over the period reveals a regular pattern of journalists killed every year. No less than 50 journalists were listed as killed in 25 out of the 30 years. If you raise the bar, you will find that 75 journalists were killed in 20 of the 30 years, and 100 journalists in 11 of the 30 years. The peak was in 2006 and 2007 and the lowest numbers were in 1998 and 2000 (37).

The untold story, however, is the risk to local journalists as most of the murdered are local beat reporters whose names do not resonate in the media. These are different from by-lined war correspondents, who knowingly risk their lives, sometimes mistaken for combatants.

In fact, nearly 75 percent of journalists killed around the world did not step on a landmine, or get shot in crossfire, or even die in a suicide bombing attack. They were instead murdered outright, such as killed by a gunman escaping on the back of a motorcycle, shot or stabbed to death near their home or office, or found dead after having been abducted and tortured.

These murders also have an impact beyond the incidents themselves. They send a signal to countless others that they or members of their family could well be next. This generates a fear that is hard to measure. Self-censorship has become routine almost everywhere.

Even in war zones, most journalists are murdered in reprisal for what they write, as opposed to being killed by the hazards of combat reporting. In Somalia, more than half of journalists killed did not die in a firefight or bombing attack; instead, they were individually murdered. In Iraq, the most dangerous nation for journalists on record, 65 percent of journalists killed since the US-led invasion were individually targeted and murdered.

The killing of local journalists is most common as nearly nine out of ten journalists were killed on the job. Many people have heard of the Russian investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot to death in the lift of her apartment. But how many people beyond the northern Mexican town of Saltillo have heard of Valentín Valdés Espinosa, a young general assignment reporter for Zócolo de Saltillo, whose tortured corpse was found in January 2010 after he reported the arrest of an alleged local drug lord? Or can we remember a single name of the 30 journalists killed in one incident during election unrest in the Philippines's Maguindanao province – the biggest single massacre of journalists.

For all these 30 years it has almost become a fact of life that the slaughter continues year in year out. The IFJ has been at the forefront of exposing the scandal of impunity and the failures of governments to bring the killers to justice. In no less than 90 per cent of journalist murders worldwide, there has been little or no prosecution whatsoever.

In two-third of the cases the killers were not identified at all and probably will never be. This means that it is almost virtually risk-free to kill a journalist – murder has become the easiest and cheapest way of silencing troublesome journalists. Occasionally, a triggerman is identified and brought to trial, but in most cases paymasters go free.

These are not just statistics. They are our friends and colleagues who have dedicated their lives to and paid the ultimate price for their work as journalists. We don't just remember them but we will pursue every case, pressing governments and law enforcement authorities to bring their murderers of journalists to justice. We have done this since 2003, for the 16 journalists who have died and others seriously wounded by US forces' fire in Iraq. In their names we do more every day to find ways of making journalism safer.

In 2006, the IFJ campaign led to the United Nations Security Council adopting resolution 1738 which called on governments to protect journalists. But the political will is still not there. Since that motion was passed some 1492 journalists were killed. A few years ago, as killings reached unprecedented numbers they attracted attention from some western governments for the first time in over three decades. However this commitment is again slipping away as the number of killings decreased in the last couple of years.

The numerous instruments adopted, both at UN and regional level, to reinforce the scope of treaty obligations, some of which address explicitly the issue of impunity are of course important. But we know their weakness – that most are non-binding and that they operate incrementally. The problem of impunity is indeed well recognised but the major hindrance for the protection of journalists derives not from the scope of the rights but from implementation deficits.

This is why the IFJ took its Convention on the Safety and Independence of Journalists to the United Nations in 2018 and is now mobilising its affiliates wordwide to help put the Convention on the agenda of the UN General Assembly.

As well as intense lobbying of international institutions and governments, the IFJ has over these years, played a unique role in helping journalists confront this ordeal, in setting up training courses in regions most in need; opening up solidarity centre in Algeria, Colombia, the Philippines, Palestine and Sri Lanka to monitor crisis situations and distribute assistance; publishing and distributing survival guides and advisories to journalists in conflict zones; and offering cheap insurance.

Being an organisation of trade unions, the IFJ has been able to have a more coherent engagement with media owners, publishers and editors, regarding their responsibility, as employers to educate their journalists in risk assessment, avoid reckless assignments and take all necessary precautions when they send them to work in dangerous environments. The adoption of an international code of conduct for the safe practice of journalism and the inclusion in the annual killed list of work-related deaths have been distinctive tools that helped in this process.

Another important and unique tool is the International Safety Fund, which has been providing emergency humanitarian assistance to journalists. Since its launch nearly 30 years ago the fund, sustained by the fund-raising efforts of IFJ unions and from donations among journalists, has paid over 3 million Euros to journalists and their families who have fled threats or been victims of violence.

During 30 years of a colossal effort to raise the bar of news safety, the IFJ and its member unions are engaged every day holding states responsible for their negligence and, in many cases, complicity in the murders of journalists.

In their names we join forces in every region to act to make journalism safer. Our strength is our unity and solidarity which we have used for the last thirty years and will continue to use to combat impunity.

This is an extract from a report published to mark international Human Rights Day:

IFJ White paper on global journalism

Launched on UN human rights day, this white paper covers issues such as global freedom of expression, working conditions, youth and gender equality.

International Convention on the Safety and Independence of Journalists and Other Media Professionals

To fight against impunity, the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) proposes a new United Nations Convention aimed at giving greater protecti...